What is a Ghazal? Meaning, History, and Popular Examples Explained

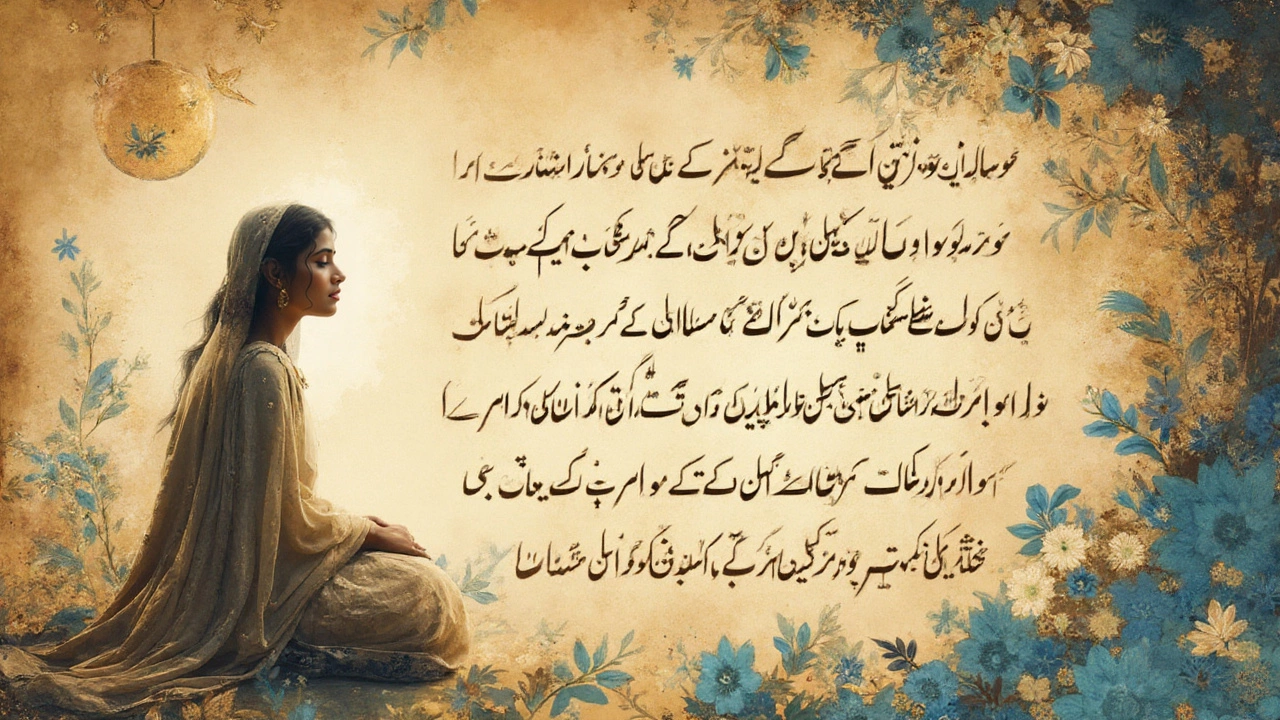

Imagine poetry that feels like a bittersweet embrace—full of longing, love, and haunting beauty. Now, picture folks from Toronto to Tehran humming the same lines, feeling the same ache and sweetness. Ghazals aren’t just poems; they’re conversations across centuries, lending words to heartbreak and hope in a way that’s totally addictive. But what is a ghazal, really? People throw the word around in music and movies, but most can’t explain what makes this form special. That’s what makes exploring ghazals so irresistible. You get drawn in by the rhythm and stuck on the feeling.

What Ghazal Really Means: Beyond Dictionary Definitions

The word “ghazal” looks exotic but rolls off the tongue with an easy grace—just "guzzle" with a twist. The term originally comes from Arabic, meaning ‘talking to women’ or ‘love talk,’ but that only hints at its layers. In reality, a ghazal is a poetic form rooted in expressing unattainable love, loss, and longing. It’s like the heart’s diary, laid out in musical couplets. But here’s the interesting bit: each couplet stands alone and tells its own tiny story, yet together, they hum the same tune of longing and separation.

Ghazals first blossomed in 7th-century Arabia as a poetic offshoot of the qasida—a long, formal ode. Then, they moved like a catchy tune across Persia, India, and even parts of Africa, picking up new dialects and flavors as they travelled. Persian poets like Hafez and Rumi shaped them, but Indian masters took the form to another level. Now, you hear ghazals set to music or read at open mics all over Toronto, and the tradition still pulses in places like Iran, Pakistan, and India.

The meaning of ghazal isn’t just about translation. It’s about emotion, structure, and a distinct way of combining words. Lovers of poetry often get hooked on the wordplay and the mingling of pain and pleasure. Many ghazals talk about forbidden love or spiritual yearning, but the rules are flexible enough to fit modern heartbreak or nostalgia, too. So when you hear someone say “that’s a ghazal,” they’re pointing to a piece of art that carries centuries of longing and a carefully built pattern that’s unique among poetic forms.

The Anatomy of a Ghazal: Form, Rules, and How It Works

Here’s where things get neat: a ghazal isn’t just a vibe—it follows rules tighter than a pop song’s chorus. A classic ghazal is made up of couplets, called "sher" in Urdu or Persian. Each couplet is two lines long and could stand alone as a tiny poem. Yet, what unites all the couplets is the rhyme and refrain, known as “radif” and “qafiya” respectively.

Let’s break this down: in every couplet of a ghazal, the last few words are repeated—the radif—while the word just before the radif usually rhymes with those in the other couplets—the qafiya. This means, if the radif is “in the rain,” then both lines in the first couplet and the second line of each following couplet end with “in the rain.” The words before it rhyme, so you get a sequence like “pain in the rain,” “remain in the rain,” “insane in the rain.” All couplets follow this, and poets often slip their name into the final couplet as a signature move.

Even more fascinating, the couplets don’t have to tell one story from start to finish. Each is standalone but echoes the same mood or theme. It’s like a playlist where every song hits a similar emotion but from a fresh perspective. That’s the real structure of a ghazal—it welcomes variety as long as the rhyme and refrain hold tight. Each ghazal has at least five couplets, but there isn’t a hard cap; some famous ghazals ramble through fifteen or more couplets, each packing its punch.

The form is exacting, so writing a proper ghazal isn’t just about spilling your feelings. You have to juggle the rhyme, the refrain, and the independence of each couplet. The discipline brings surprise: small, self-contained stories, shared heartbreaks, even jokes, get wrapped up in a musical, satisfying repetition. That’s why people get hooked—it’s both strict and free.

The Ghazal Through Time: Famous Poets, Evolution, and Global Spread

People often think of ghazals as an Asian thing, but the truth is, this form crossed borders the way music does. Back in the day, Arab poets kicked things off, but the Persians really made it shine. Hafez—a name you’ll find printed on mugs and T-shirts in Iran—filled his ghazals with mystical longing. Rumi, who wrote in Persian but is loved everywhere, used the ghazal form to talk about divine love.

By the 13th century, Persians carried the ghazal to India, where it exploded into a pop culture phenomenon. Urdu poets like Mir Taqi Mir, Ghalib, and later Faiz Ahmed Faiz made ghazals work in a brand-new linguistic landscape. Ghalib, especially, gave the ghazal a dark humor and street-smart edge that still feels fresh. Fast forward a few centuries, and you’ve got Punjabi, Turkish, and Tamil versions—the structure never collapses, just bends to local tastes.

Now, ghazals show up in Bollywood soundtracks, on Spotify playlists, and at poetry slams anywhere there’s an internet connection. In the 1970s, American poet Agha Shahid Ali dragged ghazals into English, challenging western poets like Adrienne Rich and John Hollander to play by the rules. Ali’s “Call Me Ishmael Tonight” is a must-read for anyone new to English-language ghazals.

The evolution of the ghazal reads like a mixtape—never static, always ready to soak up new rhythms, languages, and pop culture. That’s one reason why learning about ghazals is fun. You’ll spot them in unexpected places, even tucked into a Canadian winter love song or that haunting melody drifting from a nearby café.

Examples of Ghazal: Texts, Lines, and Thematic Magic

It’s one thing to talk about ghazals, but the real magic is in the lines themselves. Want to see how this thing works in daylight? Let’s check out a classic Urdu ghazal by Mirza Ghalib (translated by Aijaz Ahmad):

Hazaaron khwahishen aisi ke har khwahish pe dam nikle Bahut nikle mere armaan lekin phir bhi kam nikle A thousand desires, each so strong it could take my breath, Many were fulfilled, but still too few to settle my rest.

You can feel the longing, right? The rhyme and rhythm keep looping back, echoing the ache and hope in each line. Ghalib uses the ghazal format to put a personal stamp on universal pain. Even in English, the form shines through the translation, hinting at the original melody and discipline.

Another standout example is by Agha Shahid Ali in English:

Even the rain. I believe in the fire of love, the ferocity of rain. I believe in you. I, who can’t believe in even the rain. Or this, by his own rules: Your absence is a house at night, a secret scream. You climb the stairs and knock, but hear even the rain.

Here, the refrain “even the rain” weaves its way like a ghost through the couplets—each story separate, each feeling cascading back to the same haunting refrain. It’s easy to see how this would fit perfectly into a song, too; ghazals are made to be sung, and part of their charm is the musical repetition.

Ghazals haven’t just stayed in poetry books. Some famous ghazals became chartbusters, thanks to singers like Jagjit Singh. His “Hontho se chhoo lo tum” is basically a modern anthem, full of yearning, set in the classic ghazal style. Even if you don’t speak Urdu or Hindi, you catch the emotion—no translation required.

How to Write and Enjoy Ghazals: Tips for Beginners

So you’re reading this and thinking—you want to try your hand at ghazal-writing or just enjoy it like a pro? Good news: you don’t need perfect Urdu or a mystical muse. The secret’s in focusing on emotion, form, and restraint. Here’s what helped me (and most beginners):

- Start with a theme—love, loss, homesickness—something close to you. That’s the heart of every ghazal.

- Decide on your refrain (radif). It can be a word, two words, or even a short phrase like “in the rain” or “without you.”

- Add your pre-rhyme (qafiya): find a handful of words you can rhyme with the point before your refrain.

- Write at least five couplets. Remember: each couplet should be able to stand alone. Don’t worry if the story jumps around—that’s the ghazal’s beauty.

- Play with emotion. Lean into contradiction, unfulfilled longing, or wry observation. Different emotions in different couplets are totally cool.

- Sign your work in the final couplet. This is tradition—refer to yourself by name or a playful twist on your own identity.

- Read it out loud. Ghazals should sing—even if it’s only in your mind.

And if you just want to enjoy ghazals, don’t stress the technical stuff. Find recordings by singers like Mehdi Hassan, Jagjit Singh, or Abida Parveen and let the music hit first. Listen for the repeated refrain and notice how each couplet tugs at the same thread, differently each time. You’ll probably spot a ghazal in your favorite playlist and realize you’ve been enjoying the form without knowing the name.

Ghazals aren’t just a relic of ancient times. They’re alive and kicking—reminding us that longing, loss, and haunting love are as old as poetry itself, and as fresh as the next snowfall in Toronto. Dive into one, and you’ll hear the past echoing through today’s songs and sorrow. Whether you’re scribbling your first lines or just humming along, ghazals invite you to join a centuries-old conversation about all the things we wish for and miss the most.